Are snakes social? YES! Do snakes live in groups? SOMETIMES! Are these groups of snakes extended families? Help us find out!

As a reader of this blog, you already know that rattlesnakes are quite gregarious. Their social lives are complex; they recognize and preferentially associate with their siblings, care for their kids, and even help care for their neighbor’s kids. But the big question remains unanswered.

Many of us who monitor rattlesnake dens have speculated that they are composed of closely related individuals. Our goal is to explore this idea by examining relatedness with microsatellite DNA markers. With your help, we will find out if dens really are a rattlesnake family reunion. Our research might reveal a previously undocumented, complex social system in snakes and promote snake conservation by highlighting some very human-like behaviors.

You know you're curious about the relatedness of the snakes you've been reading about here! Check out our project on RocketHub.

And spread the word! This can be just as helpful as a financial contribution.

Monday, December 19, 2011

Friday, December 16, 2011

Squirrels and rattlesnakes have a complicated relationship. Some squirrels have developed resistance to rattlesnake venom so that an adult squirrel can survive a rattlesnake bite. Juvenile squirrels cannot, so they are often still prey to rattlesnakes. Because of their resistance, adult squirrels will confront rattlesnakes that wander near their colonies and sometimes even kill them!

For more information on rattlesnake-squirrel interactions, check out research from Rulon Clark’s lab and his student Bree Putman’s blog. Now on to Sigma’s story…

We first met Sigma on 23 April 2011 when she was basking near her den. She was named for one of her many weird blotches that is shaped like the Greek letter.

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

6 August: We return to the dens and find Sigma at large rock near her den that will be her nest site. Toward the end of her pregnancy, she settles on the west side of the rock as her main basking area, so we set up a timelapse camera there.

Between 3 and 4 September, the squirrel appears to be investigating the nest rock, but never when Sigma is on the surface.

On 5 September, Sigma and the squirrel meet:

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

The squirrel confronts Sigma

The squirrel confronts Sigma

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

6 September: Sigma sticks her head out and looks around before emerging (like Cap Mama ). About an hour later, the first of her four neonates emerge from beneath the rock:

The following video captures Sigma’s family’s first day together (warning: its kinda long, 4 minutes). Watch for the squirrel’s appearance at 12:14PM.

The squirrel does not return (that we can see) the following day and the family spends most of it on the surface:

Timelapse video of 8 September:

What starts as a peaceful day for the family was rudely interrupted by the squirrel at 11:27AM. Just before the squirrel appears in the video, Sigma turns and assumes an S-coil defensive posture typical of rattlesnakes:

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

What you can’t see in the video was captured by our overhead camera; Sigma is posturing to the squirrel just off screen:

The family immediately disappears; Sigma reemerges only after the squirrel is gone. The first neonate to emerge is quickly chased back under the nest rock by the squirrel (~11:54AM–12:01PM in the video).

9 September: After the squirrel interactions, the family seems to spend much less time on the surface (at least where the cameras can see). We recorded only one additional, indirect, interaction between Sigma and the squirrel:

As it often did when there weren’t snakes visible, the squirrel appears to be looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma returns, takes on the familiar defensive posture and appears to be rattling – although it’s difficult to be certain because the timelapse photos were taken at one-minute intervals.

Our camera continued to record at this location until 18 September and the squirrel returned about every other day, usually looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma and her four neonates were never seen together again, but we cannot say if they changed their behavior or if one or more neonates were injured or killed. One limitation of remote photography is that our knowledge is limited to what happened in view of the camera. However, it is unlikely that any of these squirrel-rattlesnake interactions would have occurred if a human observer was present. We never saw anything like this when we monitored rattlesnake families in person – have you?

Friday, December 9, 2011

You didn't think that Arizona black rattlesnakes were the only ones to take care of their kids, did you?

In a recent post on the Field Herp Forum, my friend Young Cage describes a series of observations of a family of Mexican West Coast Rattlesnakes (Crotalus basiliscus) . Young is an excellent photographer, so the post is worth checking out just to look at the pictures.

Friday, November 18, 2011

If you'd like to take a break from reading, but not rattlesnake behavior, check this out:

The Reptile Living Room: Rattlesnake Behavior with Dr. Rulon Clark

This is a great interview with my friend Rulon Clark about his research, including social behavior of timber rattlesnakes. Dr. Clark is now a professor at San Diego State University, where his lab continues to do cool stuff with rattlesnakes and other reptiles (for example, check out Strike, Rattle, & Roll).

Saturday, November 12, 2011

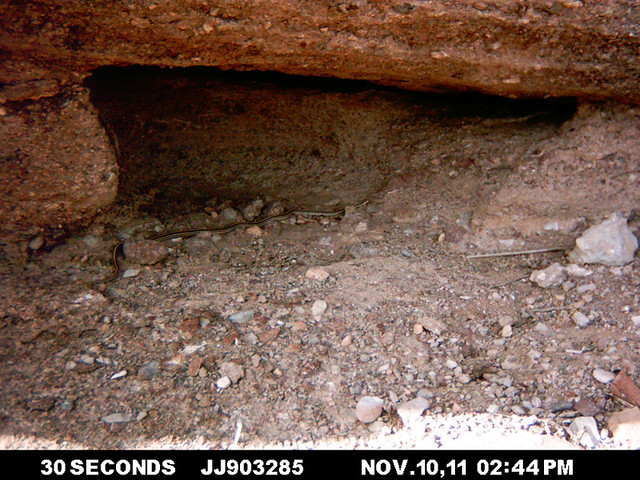

We were recently told about a new social rattlesnake den in the Galiuro Mountains. We hiked in to check it out, saw one western diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox), and decided to set up one of our timelapse cameras. The video below is from the first two days of our monitoring, and we were a little surprised at all the activity:

That video is a little long and it’s easy to miss all the visitors, so here are stills of all the reptiles we spotted.

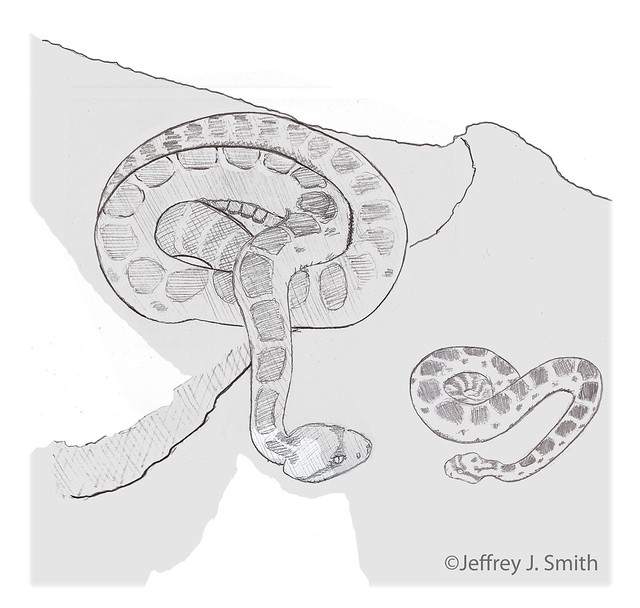

This is a juvenile Sonoran whipsnake (Coluber bilineatus). The closely related striped whipsnake (Coluber taeniatus) often shares dens with Arizona black rattlesnakes (Crotalus cerberus; see Are aggregations of Arizona black rattlesnakes stable and complex social groups?).

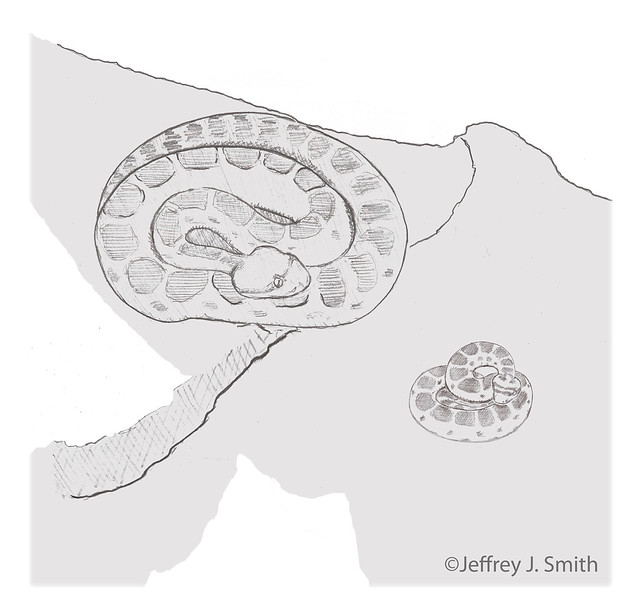

A gila monster (Heloderma suspectum)! It is not unusual for Gila monsters to share dens with western diamond-backed rattlesnakes and Sonoran Desert Tortoises (Gopherus morafkai). However, this Gila checks out the den only to turn around and leave. Could it be looking for a date? It's awfully late in the year for Gilas to be out and about.

Patch-nosed snake (Salvadora spp.) This is not a snake we have yet seen in any of our other dens. In this video, the patch-nosed appears to be checking the den out before moving on. Future videos may show if this snake continues to use the den.

There were a couple feathered reptiles here too (birds). Did we miss anyone? Who else will show up at the new den? Stay tuned...

Friday, November 11, 2011

Sorry for the interuption from our regularly scheduled program, but this is important.

Enjoy our blog posts?

Like snakes?

Then consider signing this petition to stop the unnecessary and cruel rattlesnake slaughter:

Ask Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife To End Rattlesnake Roundups

Friday, October 28, 2011

Rattlesnakes take care of their babies.

Yep, they really do. But, what does "care" look like in a snake? Do they feed their young like a mother bird? Do they keep them warm? Do they protect them from predators? With the exception of feeding, rattlesnakes care for their offspring in familiar ways. The following is a timelapse video (taken at 1 minute intervals) that illustrates a typical day for a new rattlesnake family. The large, black snake is Cap Mama, a female Arizona black rattlesnake that gestated with four other females and gave birth in late August to seven neonates. This video was taken when the neonates are just two or three days old.

Now let's look a little closer at some of the behaviors in the video:

Before the neonates emerge for the day, Cap Mama looks out as if making sure it is safe for the neonates to come out. Here she looks toward the camera...

And then she looks away from the camera. We have observed this "lookout" behavior by several different females.

The neonate in the foreground of this photo is starting to stray from the group and Cap Mama notices.

A gentle tap from Cap Mama reminds the neonate to stay with the group. We have also observed the females blocking neonates from straying too far (see A rattlesnake helper?).

The neonate responds by returning to the group and Cap Mama heads back in as well.

In this rattlesnake species, adults are darker than neonates and thus may be able to gain heat easier. By allowing neonates to sit on and near her, Cap Mama may be provisioning her offspring with heat (rattlesnakes are ectotherms: they depend on their environment for heat instead of producing their own like we do). And Cap Mama's larger size means she'll garner and release heat, perhaps even into the night when the family is tucked away in their refuge. Keeping warm helps a young snake develop, shed, and get ready to leave the nest and hunt on its own.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Priscilla, Lois, and Arli spent their pregnancy together at a rookery from May through August, 2010. Arli moved away to a private nest shortly before giving birth.

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

On 30 August 2010 we observed Priscilla (pregnant adult female) discouraging House (neonate / newborn) from potential exposure to a human predator. Because Priscilla was pregnant at this time, House had a different mother. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of helping - where an animal cares for another's offspring - in a snake. Perhaps this is why some female rattlesnakes aggregate during gestation and remain together after giving birth.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

When we left our 3 gophersnakes, Bluto had just interrupted courtship between Popeye and Olive Oyl and was biting Popeye repeatedly along his body. Popeye released his bite-grip on Olive Oyl and she fled so fast that we were unable to follow. Bluto continued biting Popeye, making him to wince but not retaliate. Instead, Popeye seeks refuge in a nearby burrow. In his fervid biting, Bluto barely notices that Popeye has escaped, actually biting himself a couple times by mistake. Finally realizing that his competitor is sidelined, Bluto resumes searching for Olive Oyl, who had a 2 ½ minute head start.

Bluto appears to be in a hurry, and while he initially showed brief reactions to close encounters with us, he no longer expresses concern. He flicks his tongue almost continuously, halting almost imperceptibly several times a second to deliver particles into his mouth. Undoubtedly, Bluto is following traces of Olive Oyl, but apparently her trail is not clear. He travels in wide loops, backtracks, and even ascends a pine tree. Perhaps Olive Oyl has passed through this area more than once. And the wind must make his search even harder!

Popeye’s urges can wait no longer. We find him peering from the burrow only 3 minutes after entering. After five more minutes, he locates Olive Oyl’s scent trail, and heads off in the same direction as the other two.

He appears to be a little more careful than Bluto, pausing to hone in on the path ahead. We try to keep tabs on both males as they move about, but we are distracted by a beautiful rattlesnake and Popeye slips away.

After about an hour Popeye reappears, coming within just a few meters of Bluto. He appears to pass Bluto, and we again lose him as he cruises on through the vegetation. Finally, at 1417, 80 minutes after we last saw her, we find Olive Oyl being courted by Popeye on open ground beneath a tree, 113 meters NE of their roadside rendezvous (see part 1). Moments later, Bluto finds the pair, Olive Oyl slips away, and conflict begins anew.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

On a humid Sonoran Desert evening we met up with Roger Repp and Gordon Schuett at their study site along with some old friends from near and far. Wandering the washes, we find a juvenile desert rodent stumbling out of a hackberry bush into the dry stream channel. It turns at our approach and manages a couple of hops away before spiraling onto one side. While at first we attribute its ungainly locomotion to its youth or perhaps being blinded by a flashlight, it soon becomes clear: its situation is dire.

Six minutes after encountering the rodent, we spot a tiger rattlesnake (Crotalus tigris) emerge from the bushes about 10 meters downstream. It’s a beautiful male with a long, intact rattle, and he’s intent on finding his meal. This next video clip shows him scent trailing his prey.

Tiger rattlesnake venom is extremely potent, and this one knows his prey couldn’t get far. His search is slow but methodical; he may turn away momentarily, but he is quick to correct course and close in on his meal. In the following video, the tiger passes very close to the rodent, visible above the stick to the left. Portions of the film are sped up 3 times.

Observations like this are infrequently witnessed. By searching on foot, keeping our minds open to what may come, and being willing to sit and watch what unfolds were we able to observe this feeding event. That, and quite a lot of luck....

In the interest of full disclosure, this snake was captured after feeding. He is now being radio-tracked by Roger and Gordon, and further updates on this snake’s life will be available on Roger’s Suizo Report, posted regularly to John Murphy's blog: http://squamates.blogspot.com/p/roger-repps-suzio-report-page.html

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

29 May 2011 – House Rock Valley – Northern Arizona

In 1996, The Peregrine Fund reintroduced California condors to northern Arizona. Once down to a mere 22 captives, there are now nearly 200 condors flying free in the southwestern US. We visited northern Arizona in hopes of finding snakes beneath soaring condors.

We learned of a trio of condors (2 males and a female) raising a chick in a cave overlooking House Rock Valley. Like Arizona black rattlesnakes, condors are social: they forage and roost in groups in which immature birds learn from experienced adults how to find food and appropriate resting sites. So it is perhaps not so unusual for a nest to have an "extra" adult male helper. We attempted to see this trio of nesting condors, but the wind howled so fiercely that we were barely able to fix a binoculared gaze on the cliffs above us. Besides, would an animal choose to be out in such unpleasant conditions? We thought not, and decided to find a place to explore that would shelter us from the wind. The valley bottom, with stands of juniper and islands of protruding sandstone, looked to be such a place.

We followed a dirt road and arbitrarily selected a place to park. We threw on our packs and crossed the road, noticing a long, dark form on the road we’d just driven. We approached to find a gophersnake (let's call him Bluto) whose chocolate ladder of blotches contrasted beautifully against a pale yellow background color. Surely realizing his vulnerability, Bluto headed directly to a juniper at the road’s edge. By the time we drew our cameras, he had found a burrow and disappeared into it. Our lamentations of his escape were short-lived, because in an adjacent sagebrush lay not one but TWO gophersnakes. Given the season and the apparent amorous nature of their entanglement, we surmised they were a male and female pair (let's call them Popeye and Olive Oyl).

After three or four minutes, the couple tired of our presence and retreated into a burrow on the opposite side of the sagebrush. Surprisingly, Bluto was already making his comeback:

Rather than try our patience against reptiles, we decide to explore the area for a while and come back later.

After about an hour we make our way back to the gophersnakes. As we walk down the road toward the spot, we see Olive Oyl meandering through the roadside vegetation, about 10 m from where we initially found her. She turned as if to cross the road, but paused before entering the barren dirt roadway.

After a couple of minutes, Popeye came cruising through the same grass she’d just passed. We watched him make several wide loops, even coming within a couple meters of her before turning away. Meanwhile, after remaining motionless for several minutes, Olive Oyl turns and moves slowly from the road. Popeye finally comes upon Olive Oyl, grasping her with his mouth behind her head (see video at 0:41). Feeling vulnerable, perhaps because of our presence, Olive Oyl is able to slowly worm to what cover is afforded by a small shrub.

Bluto enters the stage from the same area as the other two, vaguely following the same path. We watch as he loops and circles, at times retracing his path backwards. He approaches the pair within a couple meters several times, and even passes by our feet, which gives him only momentary pause. Finally, his search is over.

Bluto immediately begins biting Popeye. Finally, Popeye is induced to release his grasp of Olive Oyl. Without delay she flees and we lose track of her. Although Popeye flinches and squirms with apparent discomfort from the biting he receives, he does not appear to retaliate in kind. He escapes the assault by disappearing into a burrow in the lower left quadrant of the frame. Once Bluto realizes his rival has fled, he turns his attention to Olive Oyl, following the exact path she used to escape the dispute.

To be continued....

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Molly comes out first and coils on the left. The snake on the right is Freckle, another young adult female.

The next day, after basking in the morning sun, we find her moving among branches and rocks, and take the opportunity to swab some pink paint on her rattle using a telescoping fishing rod. Although we are able to use blotch pattern irregularities to identify individuals, a little paint on the rattle further facilitates future identification. She appears unperturbed by this, and continues her meandering to a rock several meters further from the den. Over the next two days we see Molly using the same rock for hunting by day and shelter by night.

7 May: Molly is nowhere to be found. In the spot where Molly was last seen is the unmistakable reek of skunk. While humans may perceive rattlesnakes as fierce predators, they are killed and eaten by a variety of birds and mammals, including skunks. While waiting for her first meal, did Molly fall prey to a skunk?

12 May: We spot Molly on the west side of the den, stretched out in leaf litter, poking around in the leaves with her snout. At first the behavior seems quite unusual, but then we notice a long, smooth, tail poking out of the leaves.

We are then able to capture on video a rare observation of a snake feeding in the wild and thus document the first reported predation of a Gilbert’s Skink (Plestiodon gilberti) by an Arizona black rattlesnake.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

One of our favorite snakes of 2010 has been spotted at the den! Alice was coiled next to a log a short distance away from the den the afternoon of 25 April:

|

| Alice. 25 April 2011 13:40 |

And later heading away to her hunting grounds for this year:

|

| Alice. 25 April 2011 16:13 |

Because she gave birth last year, it is unlikely that she will stick around the same area and give birth again this year. Hopefully she'll be a successful hunter this year, and next year, more babies?

|

| Alice 25 April 2011. Not so happy to see us :-( |

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

|

| Zona 29 May 2010 |

Zona was sitting on a downed log a few meters from the den where many Arizona black rattlesnakes spend their winter, and two rookeries (where female rattlesnakes give birth to their young). From the way she was positioned on the log, she was probably hunting for small lizards. Zona was photographed and her rattle marked with purple paint so that she could be identified if we crossed paths again.

27 September 2010. That fall, Zona was one of the first rattlesnakes to return to the den. We found her on the opposite side of the den, stretched out along one of the large boulders. Only a tiny bit of purple paint remained on her rattle, but several aberrancies in her pattern confirmed who this little was.

|

| Zona, 29 May (left) and 27 September (right; photo by J. Smith) 2010. Like-colored circles indicate natural pattern aberrancies used to identify this snake. |

Zona had nearly doubled in size over the intervening four months, but her dorsal blotches did not change in shape or number. We took a small sample of blood to determine her relatedness to other rattlesnakes at the den and wished her well.

April 2011. The rattlesnakes have just started basking at the den again and we've seen a few familiar faces, including Zona:

|

| Zona, 23 April 2011, emerging from the den. Can you see the same weird blotches circled in the photos above? |