"Fear of the dangers of anthropomorphism has caused ethologists to neglect many interesting phenomena, and it has become apparent that they could afford a little disciplined indulgence." (Hinde 1982)

"To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us." (de Waal 1997)

Many scientists, in their efforts to be unbiased and avoid anthropomorphism (assigning human traits to non-human animals), engage in anthropodenial (de Waal 1997). Anthropodenial is the opposite of anthropomorphism: the refusal to acknowledge humanlike characteristics of non-humans animals, which is just a bias of another sort. As indicated by Hinde and de Waal above, scientists have missed some interesting animal behaviors because of anthropodenial. (For more on this topic, check out de Waal 1997.)

For example, numerous observations of rattlesnake families dating back more than a hundred years were dismissed by the godfather of rattlesnake biology, Laurence Klauber:

Their propinquity, such as it is, does not result from any maternal solicitude; rather it is only because the refuge sought by the mother is also used as a hiding place by the young. (Klauber 1956)

In 1992, Harry Greene, Peter May, David Hardy, Jolie Sciturro, and Terence Farrell published an article on viper parental care in a peer-reviewed book. In it, they present evidence that not only do families aggregate, but mother snakes actively defend their newborns.

Was there some technological advance at that time that finally revealed this behavior to scientists? No. But, it's difficult to see what you don't look for and these authors took the time to look. They also reviewed others' observations of parental care in vipers, demonstrating that this behavior is widespread and more than mere attendance.

When we began our study of social snake behavior in 2010, we were armed with cameras, binoculars, and field notebooks. With these simple tools we managed to document behavior that was once so easily dimissed. How? We were looking for it. And maybe more importantly, we largely left the snakes alone and let them tell their story.

This is Woody's story.

We first encountered Woody (adult female Arizona black rattlesnake, Crotalus cerberus) in a pile of rocks and a jumble of downed pines in May 2010, about 150 yards from any known dens. We visited this area a number of times through the summer, and found her almost every time, relaxing near some rocks or coiled among woody debris (for which she is named). Because of her camouflage, we would have to search around for her, which sometimes brought us in close proximity, but Woody was even tempered, never rattling or attempting escape.

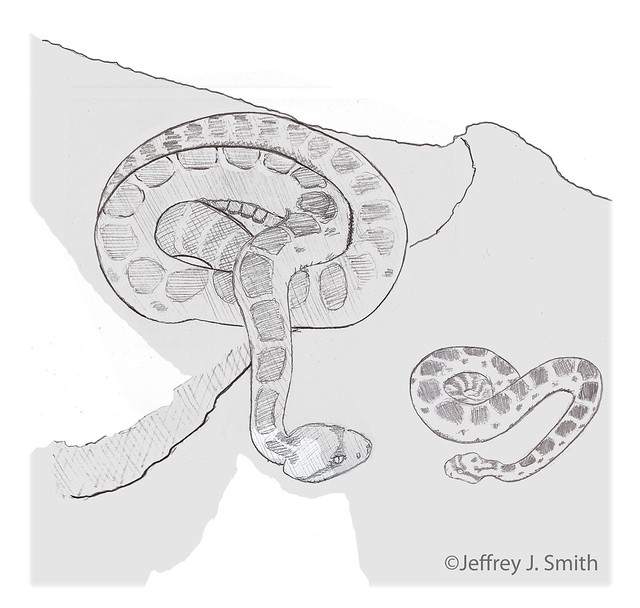

Then one day in late August, everything changed. We discovered several newborn rattlesnakes basking near Woody's favored spot. As we approached to get a closer look, but no closer than we had approached Woody so many other times, we heard muffled rattling from under the rocks. As we started snapping photos of the little ones, Woody poked her head out of her shelter and then proceeded to crawl from her refugetoward us, still rattling, and glaring directly at us. Our once-placid Woody was now fearless and wanted us to know she would not tolerate our advance. Impressed with her maternal instincts and not wanting to distress her or her young, we quickly backed off.

We were more careful in future visits to Woody's nest, but she remained a vigilant mother: rattling from within her shelter if we got too close, or assuming a defensive posture in between us and her kids (as shown in the photo above). The young caught on too, retreating into shelter if mom was upset.

Eventually the babies shed and the family split up, each trying to get a meal before it was time to enter their den for the winter. Since Woody's nest wasn't located close to a known den, we weren't sure when we would see her again. Was Woody's den located at or near her nest site? Would she show up at one of the dens we already monitored?

On the very first day we visited the dens in April 2011, we spotted Woody, basking in a popular spot with several other snakes, including some little ones that were born the previous summer. One of these juveniles turned out to be Woody's baby, Adam.

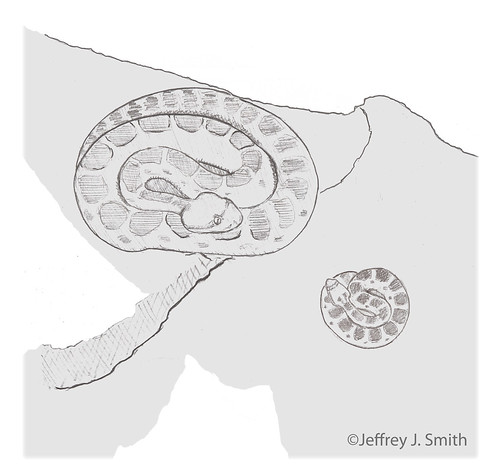

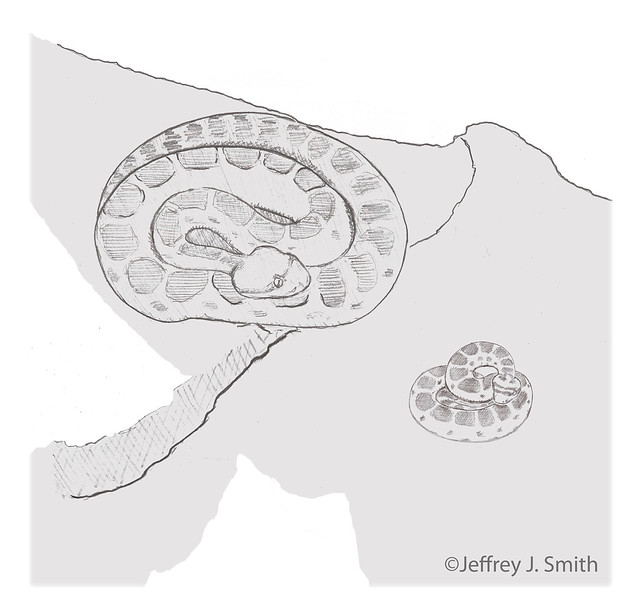

The photo on the left is Adam (newborn on left) and Woody (right), at her nest in August 2010. Woody's nest was farther away than most in 2010, but Adam found his way to their den (photo on right taken at den basking area in spring 2011). In 2011 we starting using timelapse cameras, which caught Woody and Adam as they basked together:

Although it is not unusual to see adult and juvenile rattlesnakes basking together, Woody's interest in Adam is striking. Does her maternal regard for her offspring's well-being extend beyond the nest? If her mothering is genetic and beneficial to Adam, then such care could evolve. We have seen similar behavior in another female, following a juvenile from the previous year's nest (see this post for another example of this behavior).

Many underestimate the wonders and complexity of the natural world, especially when it comes to snakes. The more we remain open to the possibilities of nature, the more we will be able to see. Even though some of their greatest admirers denied it, rattlesnakes can be caring mothers.

References

de Waal, F. B. M. 1997. Are we in anthropodenial? Discover 18:50-53.

Greene, H. W., P. May, D. L. Hardy Sr., J. M. Sciturro and T. Farrell. 2002. Parental behavior by vipers. Pp. 179-205 in G. W. Schuett, M. Hoggren, M. E. Douglas, and H. W. Greene, eds. Biology of the Vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, Utah.

Hinde, R. A. 1982. Ethology: Its Nature and Relations with Other Sciences. Oxford University Press, New York, New York.

Klauber, L. M. 1997. Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind. 2nd ed. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Sunday, January 29, 2012

It is always a little sad to say goodbye to the rattlesnake families at the end of the nesting season. It’s a difficult time for the neonates (newborns); in this population they have less than a month to find their first meal and locate a safe place to spend the winter. That’s a tall order for a two week old snake. So when the little ones disperse from the nest, we can never be sure that we’ll see them again. Today, we share stories about some of the lucky (or skillful?) neonates that survived that first winter.

Eve (large brown female rattlesnake) nested with another female, Peach (not pictured), in 2010. Together they cared for about 10 neonates, although Eve was the one most often seen on the surface with the little ones. Above you can see Bozo basking with Eve in August 2010.

Fast forward to April 2011, when the rattlesnakes are emerging from their den. Here Eve is captured by our timelapse camera coming out to bask.

Bozo follows about 20 minutes later. They crawled onto a pile of leaves in the sun:

After basking a bit with Eve, Bozo gets restless and heads off camera. A little while later, Eve appears to notice he’s gone, searches for and finds his trail (note how her head is tapping the ground), and heads off in the direction he left.

Another neonate from Eve and Peach’s nest we called Dagger. We haven’t thoroughly examined all the footage from the timelapse cameras, but so far, we have not seen Dagger at the dens in Spring 2011. So either we’ve missed him or he did not den with his nestmates, because….

Dagger was hunting near the dens in late August 2011. He hung around the area for at least a week, trying out several different spots to get a meal. Then on 1 September, our timelapse camera caught him crawling into the rear entrance of Cap Mama’s nest (she gave birth that day).

Unfortunately that is the only footage we have of Cap Mama's nest that day, so we don't know if Dagger interacted with her or the neonates.

The photo on the left is of Adam (neonate on left) and Woody (right), his mother. Woody's nest was farther away than most in 2010, about 150 yards from her den. Regardless, Adam found his way to the den where we saw him in April 2011 (photo on right). Our timelapse camera caught Woody and Adam as they basked together that day:

This is Devil Tail, who nested alone at her den in 2010. Shortly after she gave birth, a large male rattlesnake, who also dens here, visited and basked with the family:

Still image of the group:

The adult male is the large black rattlesnake at the top of the image and Devil Tail is the smaller, brown adult (mostly her tail and rattle are visible). Both of the neonates pictured here were seen at the den the following spring (2011).

Above is '520' in April 2011. Hopefully he'll be adopted and named soon!

And this is Unibrau in April 2011. Unibrau was adopted by Bill Rulon-Miller - thanks!

Barb, another of Devil Tail's neonates, is pictured here with Sigma in April 2011. Perhaps nesting right at the den increases your chances of surviving your first winter, because Devil Tail's kids seem to be doing pretty good!

If you enjoy reading these blog posts, please check out our project on RocketHub and support us financially or by spreading the word. We're raising funds to examine relatedness of this population of rattlesnakes, which will enable us to answer many questions our work has raised, including:

Are Peach and Eve, who nested together in 2010, sisters? Aunt and niece? Mother and daughter?

Was the male that visited Devil Tail the father of her neonates? Their uncle?

Supporting a research project might sound expensive, but it doesn't have to be. Through RocketHub, you can chip in as little as $5 to help us out. So skip one beer/wine/starbucks and support some cool snake research instead! Plus, you can get some cool snake stuff: rattlesnake photos, greeting cards, or adopt your very own social rattlesnake!

OK, maybe you don't have $5. But, it only takes a minute to share the link to our blog or RocketHub project on Facebook or Twitter. You have a minute, don't you? Thanks for whatever you can do to support SocialSnakes!

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Priscilla, Lois, and Arli spent their pregnancy together at a rookery from May through August, 2010. Arli moved away to a private nest shortly before giving birth.

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

On 30 August 2010 we observed Priscilla (pregnant adult female) discouraging House (neonate / newborn) from potential exposure to a human predator. Because Priscilla was pregnant at this time, House had a different mother. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of helping - where an animal cares for another's offspring - in a snake. Perhaps this is why some female rattlesnakes aggregate during gestation and remain together after giving birth.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.

Saturday, February 5, 2011

Memorial Day Weekend 2010. Alice is a big, beautiful, dark female Arizona black rattlesnake with mustard yellow scales outlining each dorsal blotch. We first encountered her ~20 meters from a known rattlesnake den. Several of our party walked right by before we discovered her, coiled at an opening beneath a boulder, without her rattling or stirring. This is actually pretty typical behavior for rattlesnakes. Their primary defense is to remain still, silent, and rely on camouflage.

Alice was healthy-looking, and we could tell by her distended posterior that she’d be expecting babies in a few months. She was marked with lavender paint on her rattle and we noted several pattern aberrancies (see below). For the next few days Alice remained quietly coiled by her boulder as we passed by to monitor other snakes.

|

| The two basal (closest to the body) segments of the rattle are painted lavender - it is purposely difficult to see so that she is not too visible to potentials predators. |

We returned on 27 July to find Alice coiled in nearly the same spot we left her two months prior. With the approach of birthing season (late August – early September), we repeated visits weekly, and Alice would reliably be found contently coiled in dappled sunlight. We respected her space, using binoculars and telephotography to verify her paint and markings, and she appeared unfazed by these activities. Despite our sporadic visits, it is unlikely that we missed a lot of Alice’s activity; pregnant rattlesnakes usually don’t feed or don’t make large movements.

A rattlesnake hunts by finding a promising spot to ambush prey, and then sits and waits with an ‘S’ curve in its neck, ready to spring when a lizard, bird or rodent happens across its strike zone. Critical to an ambush is unpredictability; a hunting rattlesnake might try several spots in a small area before moving off to a new hunting patch. We don’t know when Alice might have eaten last, or whether she would if a meal presented itself. But she was never seen in a hunting posture or with any evidence of recently ingested food item. So it is likely that Alice did not feed during her pregnancy, which is typical of most rattlesnakes.

Alice’s boulder complex has a footprint little bigger than a compact car. Despite its small size, we only observed her using a handful of spots during a couple of dozen observations, and she did so like clockwork. She would emerge in the morning at the mouth of a large opening, around 10am when the sun was angled above the pinetops. As the sun arced higher, she would retreat partially or completely into the deep shade of her boulder to keep from overheating. By afternoon, as the sun again filtered through trees to the west, Alice would emerge onto a west-facing rock ledge. Here she would stay until she had gained all the heat she could, and around 5pm she would retreat back under her boulder for the evening. On cool or cloudy days, she would be visible all day, ready to drink up any drops of rain that might collect on her or the granite walls of her home.

Alice’s home was a temple to the sun, and her daily ritual was an expression of her strong maternal instinct. Snakes are ectotherms; they depend on their environment to achieve and maintain a favorable body temperature. And maintaining a proper body temperature is especially important for a pregnant snake like Alice, whose babies’ development and timely delivery require as consistent warmth as mom can provide. Unfortunately, Alice lives in a cool, shady forest where staying warm is a challenge.

|

| Despite apparently not feeding, Alice grew fatter and fatter over the next few weeks. |

Indeed the lucky girl had already acquired her first meal, likely one of the many newly hatched lizards. A week or two before the rattlesnakes were born three different species of lizards (Greater short-horned lizard, Phrynosoma hernandesi; Plateau fence lizard, Sceloporus tristichus; Plateau striped whiptail, Aspidoscelis velox) hatched and this area was literally crawling with lizards. Could this abundance of food, perfectly sized for neonate rattlesnakes, be the reason Alice chose this place to have her family? Will this little girl return to birth her young here in a few years?