Mother's day is a much bigger deal than Father's day. Why? Well, there's just something extra special about mom (sorry Dad!). So, today's post is about an under-appreciated group of moms (you guessed it), Arizona black rattlesnakes!

Human moms - you think you have it tough? Rattlesnake maternal duties may only last a couple weeks, but during that time they may have to protect their kids from extreme temperatures, a suite of predators, annoying (and deadly?) squirrels, and clumsy humans with cameras... By the time they give birth, mother rattlesnakes likely haven't eaten in weeks or even months, but they wait another couple weeks to give full attention to their newborns. So here's to you rattlesnake mommies!

We'll start with the most famous of all, Cap Mama, who showed us what a typical day is like for a new rattlesnake family:

For an explanation of the behaviors seen in that video, check out this post.

What a beautiful family she has!

Sigma may have been one of our smaller mothers, but what she lacked in size she made up for in bravery:

Check out the full story of Sigma's squirrel battles here.

We've been lucky enough to see Woody and Alice with two different litters.

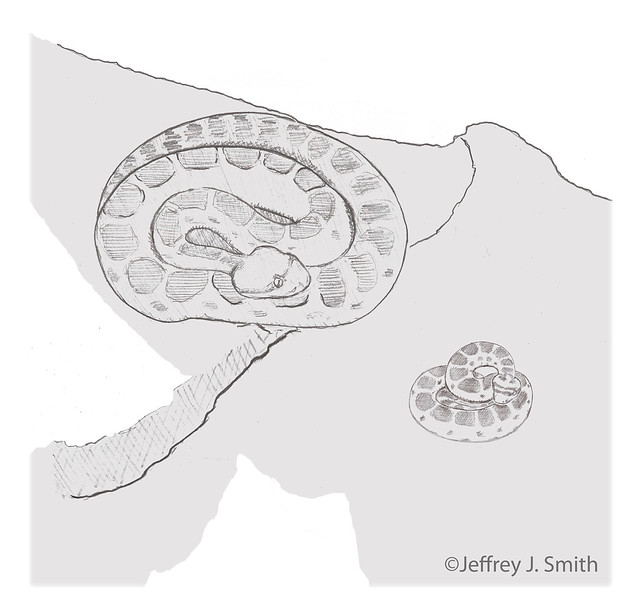

Alice's family, 2010

Alice's family, 2012

Woody's family, 2012. You can watch more timelapse videos of Woody's family here and here.

Every mom needs a day off. So the lucky (or smart?) rattlesnakes that nest in groups help each other out with maternal duties. If one is still pregnant, and thus needs to be on the surface basking, she attend to the newborns while the new mother stays in cover for a well-deserved rest. Priscilla was the first rattlesnake we observed exhibiting this baby-sitting behavior.

You can read more about Priscilla and House here.

You can read more about Priscilla and House here.

Male rattlesnakes occasionally help out in this way too. Although we've never observed any active care or protective behavior from males, just the presence of a large rattlesnake may be enough to deter some predators.

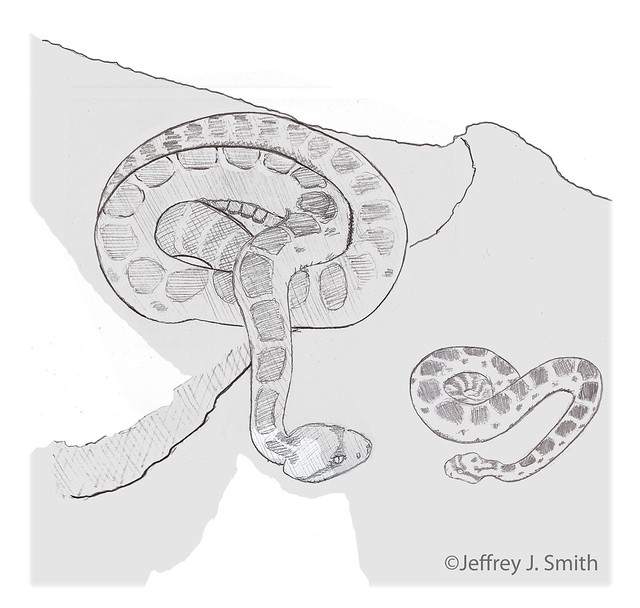

Still image of the group:

Green Male (adult male) is the large black rattlesnake at the top of the image and the mother (Devil Tail) is the smaller, brown adult (mostly her tail and rattle are visible).

A handful of newborns follow Roger (adult male) out of the nest entrance to a preferred basking spot.

Sometimes the youngest (smallest) mom gets stuck with the surface duties of caring for the newborns. Eve was the smallest of the pair of snakes that nested at this site; we saw her often on the surface with way too many babies to have all been her own. The older (larger) female was rarely seen on the surface with the newborns.

This is the first Mother's day in years that we haven't spent at dens with our rattlesnake mothers-to-be. But, as of last week, two (Persephone and Luna) of our three Muleshoe rattlesnakes are still near their dens. While this is atypical rattlesnake behavior in general, it is characteristic of pregnant Arizona black rattlesnakes. So maybe we'll have a couple more names to add to this list next year!

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

"Fear of the dangers of anthropomorphism has caused ethologists to neglect many interesting phenomena, and it has become apparent that they could afford a little disciplined indulgence." (Hinde 1982)

"To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us." (de Waal 1997)

Many scientists, in their efforts to be unbiased and avoid anthropomorphism (assigning human traits to non-human animals), engage in anthropodenial (de Waal 1997). Anthropodenial is the opposite of anthropomorphism: the refusal to acknowledge humanlike characteristics of non-humans animals, which is just a bias of another sort. As indicated by Hinde and de Waal above, scientists have missed some interesting animal behaviors because of anthropodenial. (For more on this topic, check out de Waal 1997.)

For example, numerous observations of rattlesnake families dating back more than a hundred years were dismissed by the godfather of rattlesnake biology, Laurence Klauber:

Their propinquity, such as it is, does not result from any maternal solicitude; rather it is only because the refuge sought by the mother is also used as a hiding place by the young. (Klauber 1956)

In 1992, Harry Greene, Peter May, David Hardy, Jolie Sciturro, and Terence Farrell published an article on viper parental care in a peer-reviewed book. In it, they present evidence that not only do families aggregate, but mother snakes actively defend their newborns.

Was there some technological advance at that time that finally revealed this behavior to scientists? No. But, it's difficult to see what you don't look for and these authors took the time to look. They also reviewed others' observations of parental care in vipers, demonstrating that this behavior is widespread and more than mere attendance.

When we began our study of social snake behavior in 2010, we were armed with cameras, binoculars, and field notebooks. With these simple tools we managed to document behavior that was once so easily dimissed. How? We were looking for it. And maybe more importantly, we largely left the snakes alone and let them tell their story.

This is Woody's story.

We first encountered Woody (adult female Arizona black rattlesnake, Crotalus cerberus) in a pile of rocks and a jumble of downed pines in May 2010, about 150 yards from any known dens. We visited this area a number of times through the summer, and found her almost every time, relaxing near some rocks or coiled among woody debris (for which she is named). Because of her camouflage, we would have to search around for her, which sometimes brought us in close proximity, but Woody was even tempered, never rattling or attempting escape.

Then one day in late August, everything changed. We discovered several newborn rattlesnakes basking near Woody's favored spot. As we approached to get a closer look, but no closer than we had approached Woody so many other times, we heard muffled rattling from under the rocks. As we started snapping photos of the little ones, Woody poked her head out of her shelter and then proceeded to crawl from her refugetoward us, still rattling, and glaring directly at us. Our once-placid Woody was now fearless and wanted us to know she would not tolerate our advance. Impressed with her maternal instincts and not wanting to distress her or her young, we quickly backed off.

We were more careful in future visits to Woody's nest, but she remained a vigilant mother: rattling from within her shelter if we got too close, or assuming a defensive posture in between us and her kids (as shown in the photo above). The young caught on too, retreating into shelter if mom was upset.

Eventually the babies shed and the family split up, each trying to get a meal before it was time to enter their den for the winter. Since Woody's nest wasn't located close to a known den, we weren't sure when we would see her again. Was Woody's den located at or near her nest site? Would she show up at one of the dens we already monitored?

On the very first day we visited the dens in April 2011, we spotted Woody, basking in a popular spot with several other snakes, including some little ones that were born the previous summer. One of these juveniles turned out to be Woody's baby, Adam.

The photo on the left is Adam (newborn on left) and Woody (right), at her nest in August 2010. Woody's nest was farther away than most in 2010, but Adam found his way to their den (photo on right taken at den basking area in spring 2011). In 2011 we starting using timelapse cameras, which caught Woody and Adam as they basked together:

Although it is not unusual to see adult and juvenile rattlesnakes basking together, Woody's interest in Adam is striking. Does her maternal regard for her offspring's well-being extend beyond the nest? If her mothering is genetic and beneficial to Adam, then such care could evolve. We have seen similar behavior in another female, following a juvenile from the previous year's nest (see this post for another example of this behavior).

Many underestimate the wonders and complexity of the natural world, especially when it comes to snakes. The more we remain open to the possibilities of nature, the more we will be able to see. Even though some of their greatest admirers denied it, rattlesnakes can be caring mothers.

References

de Waal, F. B. M. 1997. Are we in anthropodenial? Discover 18:50-53.

Greene, H. W., P. May, D. L. Hardy Sr., J. M. Sciturro and T. Farrell. 2002. Parental behavior by vipers. Pp. 179-205 in G. W. Schuett, M. Hoggren, M. E. Douglas, and H. W. Greene, eds. Biology of the Vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, Utah.

Hinde, R. A. 1982. Ethology: Its Nature and Relations with Other Sciences. Oxford University Press, New York, New York.

Klauber, L. M. 1997. Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind. 2nd ed. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

It is always a little sad to say goodbye to the rattlesnake families at the end of the nesting season. It’s a difficult time for the neonates (newborns); in this population they have less than a month to find their first meal and locate a safe place to spend the winter. That’s a tall order for a two week old snake. So when the little ones disperse from the nest, we can never be sure that we’ll see them again. Today, we share stories about some of the lucky (or skillful?) neonates that survived that first winter.

Eve (large brown female rattlesnake) nested with another female, Peach (not pictured), in 2010. Together they cared for about 10 neonates, although Eve was the one most often seen on the surface with the little ones. Above you can see Bozo basking with Eve in August 2010.

Fast forward to April 2011, when the rattlesnakes are emerging from their den. Here Eve is captured by our timelapse camera coming out to bask.

Bozo follows about 20 minutes later. They crawled onto a pile of leaves in the sun:

After basking a bit with Eve, Bozo gets restless and heads off camera. A little while later, Eve appears to notice he’s gone, searches for and finds his trail (note how her head is tapping the ground), and heads off in the direction he left.

Another neonate from Eve and Peach’s nest we called Dagger. We haven’t thoroughly examined all the footage from the timelapse cameras, but so far, we have not seen Dagger at the dens in Spring 2011. So either we’ve missed him or he did not den with his nestmates, because….

Dagger was hunting near the dens in late August 2011. He hung around the area for at least a week, trying out several different spots to get a meal. Then on 1 September, our timelapse camera caught him crawling into the rear entrance of Cap Mama’s nest (she gave birth that day).

Unfortunately that is the only footage we have of Cap Mama's nest that day, so we don't know if Dagger interacted with her or the neonates.

The photo on the left is of Adam (neonate on left) and Woody (right), his mother. Woody's nest was farther away than most in 2010, about 150 yards from her den. Regardless, Adam found his way to the den where we saw him in April 2011 (photo on right). Our timelapse camera caught Woody and Adam as they basked together that day:

This is Devil Tail, who nested alone at her den in 2010. Shortly after she gave birth, a large male rattlesnake, who also dens here, visited and basked with the family:

Still image of the group:

The adult male is the large black rattlesnake at the top of the image and Devil Tail is the smaller, brown adult (mostly her tail and rattle are visible). Both of the neonates pictured here were seen at the den the following spring (2011).

Above is '520' in April 2011. Hopefully he'll be adopted and named soon!

And this is Unibrau in April 2011. Unibrau was adopted by Bill Rulon-Miller - thanks!

Barb, another of Devil Tail's neonates, is pictured here with Sigma in April 2011. Perhaps nesting right at the den increases your chances of surviving your first winter, because Devil Tail's kids seem to be doing pretty good!

If you enjoy reading these blog posts, please check out our project on RocketHub and support us financially or by spreading the word. We're raising funds to examine relatedness of this population of rattlesnakes, which will enable us to answer many questions our work has raised, including:

Are Peach and Eve, who nested together in 2010, sisters? Aunt and niece? Mother and daughter?

Was the male that visited Devil Tail the father of her neonates? Their uncle?

Supporting a research project might sound expensive, but it doesn't have to be. Through RocketHub, you can chip in as little as $5 to help us out. So skip one beer/wine/starbucks and support some cool snake research instead! Plus, you can get some cool snake stuff: rattlesnake photos, greeting cards, or adopt your very own social rattlesnake!

OK, maybe you don't have $5. But, it only takes a minute to share the link to our blog or RocketHub project on Facebook or Twitter. You have a minute, don't you? Thanks for whatever you can do to support SocialSnakes!

Friday, December 16, 2011

Squirrels and rattlesnakes have a complicated relationship. Some squirrels have developed resistance to rattlesnake venom so that an adult squirrel can survive a rattlesnake bite. Juvenile squirrels cannot, so they are often still prey to rattlesnakes. Because of their resistance, adult squirrels will confront rattlesnakes that wander near their colonies and sometimes even kill them!

For more information on rattlesnake-squirrel interactions, check out research from Rulon Clark’s lab and his student Bree Putman’s blog. Now on to Sigma’s story…

We first met Sigma on 23 April 2011 when she was basking near her den. She was named for one of her many weird blotches that is shaped like the Greek letter.

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

6 August: We return to the dens and find Sigma at large rock near her den that will be her nest site. Toward the end of her pregnancy, she settles on the west side of the rock as her main basking area, so we set up a timelapse camera there.

Between 3 and 4 September, the squirrel appears to be investigating the nest rock, but never when Sigma is on the surface.

On 5 September, Sigma and the squirrel meet:

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

The squirrel confronts Sigma

The squirrel confronts Sigma

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

6 September: Sigma sticks her head out and looks around before emerging (like Cap Mama ). About an hour later, the first of her four neonates emerge from beneath the rock:

The following video captures Sigma’s family’s first day together (warning: its kinda long, 4 minutes). Watch for the squirrel’s appearance at 12:14PM.

The squirrel does not return (that we can see) the following day and the family spends most of it on the surface:

Timelapse video of 8 September:

What starts as a peaceful day for the family was rudely interrupted by the squirrel at 11:27AM. Just before the squirrel appears in the video, Sigma turns and assumes an S-coil defensive posture typical of rattlesnakes:

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

What you can’t see in the video was captured by our overhead camera; Sigma is posturing to the squirrel just off screen:

The family immediately disappears; Sigma reemerges only after the squirrel is gone. The first neonate to emerge is quickly chased back under the nest rock by the squirrel (~11:54AM–12:01PM in the video).

9 September: After the squirrel interactions, the family seems to spend much less time on the surface (at least where the cameras can see). We recorded only one additional, indirect, interaction between Sigma and the squirrel:

As it often did when there weren’t snakes visible, the squirrel appears to be looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma returns, takes on the familiar defensive posture and appears to be rattling – although it’s difficult to be certain because the timelapse photos were taken at one-minute intervals.

Our camera continued to record at this location until 18 September and the squirrel returned about every other day, usually looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma and her four neonates were never seen together again, but we cannot say if they changed their behavior or if one or more neonates were injured or killed. One limitation of remote photography is that our knowledge is limited to what happened in view of the camera. However, it is unlikely that any of these squirrel-rattlesnake interactions would have occurred if a human observer was present. We never saw anything like this when we monitored rattlesnake families in person – have you?

Friday, December 9, 2011

You didn't think that Arizona black rattlesnakes were the only ones to take care of their kids, did you?

In a recent post on the Field Herp Forum, my friend Young Cage describes a series of observations of a family of Mexican West Coast Rattlesnakes (Crotalus basiliscus) . Young is an excellent photographer, so the post is worth checking out just to look at the pictures.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Rattlesnakes take care of their babies.

Yep, they really do. But, what does "care" look like in a snake? Do they feed their young like a mother bird? Do they keep them warm? Do they protect them from predators? With the exception of feeding, rattlesnakes care for their offspring in familiar ways. The following is a timelapse video (taken at 1 minute intervals) that illustrates a typical day for a new rattlesnake family. The large, black snake is Cap Mama, a female Arizona black rattlesnake that gestated with four other females and gave birth in late August to seven neonates. This video was taken when the neonates are just two or three days old.

Now let's look a little closer at some of the behaviors in the video:

Before the neonates emerge for the day, Cap Mama looks out as if making sure it is safe for the neonates to come out. Here she looks toward the camera...

And then she looks away from the camera. We have observed this "lookout" behavior by several different females.

The neonate in the foreground of this photo is starting to stray from the group and Cap Mama notices.

A gentle tap from Cap Mama reminds the neonate to stay with the group. We have also observed the females blocking neonates from straying too far (see A rattlesnake helper?).

The neonate responds by returning to the group and Cap Mama heads back in as well.

In this rattlesnake species, adults are darker than neonates and thus may be able to gain heat easier. By allowing neonates to sit on and near her, Cap Mama may be provisioning her offspring with heat (rattlesnakes are ectotherms: they depend on their environment for heat instead of producing their own like we do). And Cap Mama's larger size means she'll garner and release heat, perhaps even into the night when the family is tucked away in their refuge. Keeping warm helps a young snake develop, shed, and get ready to leave the nest and hunt on its own.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Priscilla, Lois, and Arli spent their pregnancy together at a rookery from May through August, 2010. Arli moved away to a private nest shortly before giving birth.

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

Priscilla & House, 1 September 2010

On 30 August 2010 we observed Priscilla (pregnant adult female) discouraging House (neonate / newborn) from potential exposure to a human predator. Because Priscilla was pregnant at this time, House had a different mother. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of helping - where an animal cares for another's offspring - in a snake. Perhaps this is why some female rattlesnakes aggregate during gestation and remain together after giving birth.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:27 Priscilla (adult female) and House (neonate) are at rest in a shaded rock shelter.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:28 House moves restlessly in cover and then begins to move toward open ground.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:29 Priscilla swiftly confronts House before he wanders away from cover; her posture is unusually rigid.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.

15:31 House stops, turns around, and coils in cover. Priscilla's head returns to her coils.