Are snakes social? YES! Do snakes live in groups? SOMETIMES! Are these groups of snakes extended families? Help us find out!

As a reader of this blog, you already know that rattlesnakes are quite gregarious. Their social lives are complex; they recognize and preferentially associate with their siblings, care for their kids, and even help care for their neighbor’s kids. But the big question remains unanswered.

Many of us who monitor rattlesnake dens have speculated that they are composed of closely related individuals. Our goal is to explore this idea by examining relatedness with microsatellite DNA markers. With your help, we will find out if dens really are a rattlesnake family reunion. Our research might reveal a previously undocumented, complex social system in snakes and promote snake conservation by highlighting some very human-like behaviors.

You know you're curious about the relatedness of the snakes you've been reading about here! Check out our project on RocketHub.

And spread the word! This can be just as helpful as a financial contribution.

Monday, December 19, 2011

Friday, December 16, 2011

Squirrels and rattlesnakes have a complicated relationship. Some squirrels have developed resistance to rattlesnake venom so that an adult squirrel can survive a rattlesnake bite. Juvenile squirrels cannot, so they are often still prey to rattlesnakes. Because of their resistance, adult squirrels will confront rattlesnakes that wander near their colonies and sometimes even kill them!

For more information on rattlesnake-squirrel interactions, check out research from Rulon Clark’s lab and his student Bree Putman’s blog. Now on to Sigma’s story…

We first met Sigma on 23 April 2011 when she was basking near her den. She was named for one of her many weird blotches that is shaped like the Greek letter.

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

Sigma and Barb, 24 April 2011. Barb was born here, to another female (Devil Tail), the previous September (2010).

6 August: We return to the dens and find Sigma at large rock near her den that will be her nest site. Toward the end of her pregnancy, she settles on the west side of the rock as her main basking area, so we set up a timelapse camera there.

Between 3 and 4 September, the squirrel appears to be investigating the nest rock, but never when Sigma is on the surface.

On 5 September, Sigma and the squirrel meet:

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

Sigma (at end of arrow) emerging for the first time that day

The squirrel confronts Sigma

The squirrel confronts Sigma

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

Sigma immediately retreats beneath her nest rock

6 September: Sigma sticks her head out and looks around before emerging (like Cap Mama ). About an hour later, the first of her four neonates emerge from beneath the rock:

The following video captures Sigma’s family’s first day together (warning: its kinda long, 4 minutes). Watch for the squirrel’s appearance at 12:14PM.

The squirrel does not return (that we can see) the following day and the family spends most of it on the surface:

Timelapse video of 8 September:

What starts as a peaceful day for the family was rudely interrupted by the squirrel at 11:27AM. Just before the squirrel appears in the video, Sigma turns and assumes an S-coil defensive posture typical of rattlesnakes:

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma at rest with her family

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

Sigma turns, expands her body to look as large as possible, and assumes a ready-to-strike (S-coil) defensive posture.

What you can’t see in the video was captured by our overhead camera; Sigma is posturing to the squirrel just off screen:

The family immediately disappears; Sigma reemerges only after the squirrel is gone. The first neonate to emerge is quickly chased back under the nest rock by the squirrel (~11:54AM–12:01PM in the video).

9 September: After the squirrel interactions, the family seems to spend much less time on the surface (at least where the cameras can see). We recorded only one additional, indirect, interaction between Sigma and the squirrel:

As it often did when there weren’t snakes visible, the squirrel appears to be looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma returns, takes on the familiar defensive posture and appears to be rattling – although it’s difficult to be certain because the timelapse photos were taken at one-minute intervals.

Our camera continued to record at this location until 18 September and the squirrel returned about every other day, usually looking underneath the nest rock. Sigma and her four neonates were never seen together again, but we cannot say if they changed their behavior or if one or more neonates were injured or killed. One limitation of remote photography is that our knowledge is limited to what happened in view of the camera. However, it is unlikely that any of these squirrel-rattlesnake interactions would have occurred if a human observer was present. We never saw anything like this when we monitored rattlesnake families in person – have you?

Friday, December 9, 2011

You didn't think that Arizona black rattlesnakes were the only ones to take care of their kids, did you?

In a recent post on the Field Herp Forum, my friend Young Cage describes a series of observations of a family of Mexican West Coast Rattlesnakes (Crotalus basiliscus) . Young is an excellent photographer, so the post is worth checking out just to look at the pictures.

Friday, November 18, 2011

If you'd like to take a break from reading, but not rattlesnake behavior, check this out:

The Reptile Living Room: Rattlesnake Behavior with Dr. Rulon Clark

This is a great interview with my friend Rulon Clark about his research, including social behavior of timber rattlesnakes. Dr. Clark is now a professor at San Diego State University, where his lab continues to do cool stuff with rattlesnakes and other reptiles (for example, check out Strike, Rattle, & Roll).

Saturday, November 12, 2011

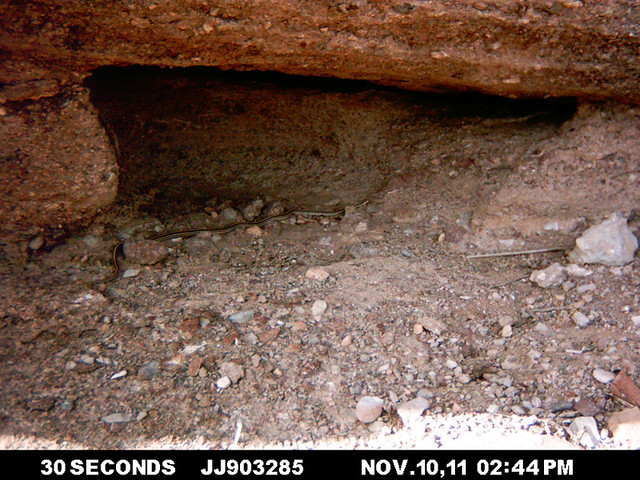

We were recently told about a new social rattlesnake den in the Galiuro Mountains. We hiked in to check it out, saw one western diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox), and decided to set up one of our timelapse cameras. The video below is from the first two days of our monitoring, and we were a little surprised at all the activity:

That video is a little long and it’s easy to miss all the visitors, so here are stills of all the reptiles we spotted.

This is a juvenile Sonoran whipsnake (Coluber bilineatus). The closely related striped whipsnake (Coluber taeniatus) often shares dens with Arizona black rattlesnakes (Crotalus cerberus; see Are aggregations of Arizona black rattlesnakes stable and complex social groups?).

A gila monster (Heloderma suspectum)! It is not unusual for Gila monsters to share dens with western diamond-backed rattlesnakes and Sonoran Desert Tortoises (Gopherus morafkai). However, this Gila checks out the den only to turn around and leave. Could it be looking for a date? It's awfully late in the year for Gilas to be out and about.

Patch-nosed snake (Salvadora spp.) This is not a snake we have yet seen in any of our other dens. In this video, the patch-nosed appears to be checking the den out before moving on. Future videos may show if this snake continues to use the den.

There were a couple feathered reptiles here too (birds). Did we miss anyone? Who else will show up at the new den? Stay tuned...

Friday, November 11, 2011

Sorry for the interuption from our regularly scheduled program, but this is important.

Enjoy our blog posts?

Like snakes?

Then consider signing this petition to stop the unnecessary and cruel rattlesnake slaughter:

Ask Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife To End Rattlesnake Roundups

Friday, October 28, 2011

Rattlesnakes take care of their babies.

Yep, they really do. But, what does "care" look like in a snake? Do they feed their young like a mother bird? Do they keep them warm? Do they protect them from predators? With the exception of feeding, rattlesnakes care for their offspring in familiar ways. The following is a timelapse video (taken at 1 minute intervals) that illustrates a typical day for a new rattlesnake family. The large, black snake is Cap Mama, a female Arizona black rattlesnake that gestated with four other females and gave birth in late August to seven neonates. This video was taken when the neonates are just two or three days old.

Now let's look a little closer at some of the behaviors in the video:

Before the neonates emerge for the day, Cap Mama looks out as if making sure it is safe for the neonates to come out. Here she looks toward the camera...

And then she looks away from the camera. We have observed this "lookout" behavior by several different females.

The neonate in the foreground of this photo is starting to stray from the group and Cap Mama notices.

A gentle tap from Cap Mama reminds the neonate to stay with the group. We have also observed the females blocking neonates from straying too far (see A rattlesnake helper?).

The neonate responds by returning to the group and Cap Mama heads back in as well.

In this rattlesnake species, adults are darker than neonates and thus may be able to gain heat easier. By allowing neonates to sit on and near her, Cap Mama may be provisioning her offspring with heat (rattlesnakes are ectotherms: they depend on their environment for heat instead of producing their own like we do). And Cap Mama's larger size means she'll garner and release heat, perhaps even into the night when the family is tucked away in their refuge. Keeping warm helps a young snake develop, shed, and get ready to leave the nest and hunt on its own.